Dialogue January-March, 2007, Volume 8 No. 3

India’s Interface with East Asia

Lokesh Chandra*

Cultural Interflow between India and China

The last twentythree centuries have seen a continuing cultural interflow between the Western paradise that is India and the Celestial Kingdom that is China. The rustling breeze of Buddhist fragrance has awakened the mindscape of both countries, endowing them with the web of thought, the harmony of art, the magnificent colour of murals and sculptures, incarnating a new life and sinking into the sensitivities of our peoples deep-reaching muscles of mystery, draped in the intimacy of the mind. The first contacts were made by Buddhist scholars from India who appeared in the Chinese capital in 217 B.C. under the Tsin dynasty. Contacts during the Tsin dynasty are a fair possibility as the Sanskrit word for Cathy is China, as such was the dynastic name Tsin heard by the Indians.

In 138 B.C. Chang Ch’ien was an envoy of the Chinese Emperor to India. He took back musical instruments and Maha-Tukhara melodies to the Chinese capital Ch’ang-an. The son-in-law of the Emperor Wu-ti, he wrote 28 new tunes based on this melody which were played as military music. Along with Buddhism, the Serindians introduced milk to China. The Chinese ideograph lo, pronounced lak in ancient times, which meant varied kinds of fermented milk products, was a loan from Indo-European (Latin lac-tic).

The Yuechi rulers presented Sanskrit texts to the Chinese court in 2 B.C. The first historically owned Buddhist masters arrived in China in A.D. 67. The Han Emperor Ming-ti dreamt of a golden person. On enquiry from his courtiers he learnt that he was the Buddha. He sent ambassadors to the West (i.e. India) to invite Buddhist teachers. They returned with Dharmaraksha and Kashyapa Matanga. They arrived on white horses laden with scriptures and sacred relics. The first Buddhist monastery was built for them on Imperial orders and it came to be known as “The White Horse Monastery” (Po-ma-sse). They wrote “The Sutra of 42 Sections” to provide a guide to the ideas of Buddhism and to the conduct of monks. This monastery exists to this day and the cenotaphs of the two Indian teachers can be seen in its precincts.

In the reign Kanishka bilateral relations entered a new phase in economic, political and cultural domains. Kanishka as the greatest of Kushan emperors symbolized his international status by the adoption of four titles: Devaputra or Son of Heaven from China, Shaonana Shao or King of Kings from Persia, Kaisara or Caesar from Rome, and Maharaja of India, signifying the imperial dignity of the four superpowers of the time: China, Persia, Rome and India. He played a major role in the dissemination of Buddhism to China. The policy of cultural internationalism enunciated by Ashoka found its prime efflorescence in the reign of Kanishka. Hsuan-tsang relates that Kanishka defeated the Chinese in Central Asia and Chinese princes were sent as hostages. Territories were allotted to them in Punjab which were known as Cina-bhukti, an area that Hsuan-tsang visited in the seventh century. Now it is a village Chiniyari near Amritsar, and Chiniot from Cinakota. The Chinese princes introduced two new fruits to India: the peach and the pear. They came to be known respectively as cînânî and cînarâjaputra which means “Peach the Chinese Princess” and “Pear the Chinese Prince”.

In India paper had been manufactured out of cotton, and out of silk in Han China. With the introduction of Buddhism cotton also became a component of paper, as is evident from the old lexicon entitled Ku-chin tzu-ku where silk radical of the character for paper is replaced by the radical for cotton. Cotton cultivation had been introduced from Kashmir and Bengal to China in as early as the second century B.C.

The sandy vastness that led to India was the path of sutras, first and foremost the way of texts and translators, of scriptures and schools of thought, of the triumphs of Buddhism as the mental and material culture of East Asia. The development of Buddhist temple architecture, new stylistic features in Chinese that arose from translations of Buddhist texts, the Buddhist plurality of inhabited worlds as opposed to the Chinese earth-centred worldview, and various elements of cultural transmission, opened up Sinocentrism to wider horizons. The several people inhabiting the route participated in the cultural exchange for a millennium. The earliest and most celebrated of the masters was the Parthian An Shih-kao who orgnaised the first translation team, after his arrival at Loyang in AD 148.

As early as in 251 A.D. we find Kaang Seng-hui rendering the Jataka form of the Ramayana into Chinese, and in 472 A.D. appeared another Chinese translation of the Avadana of Dasratha from a lost Sanskrit text by Kekaya. A long tradition in narrative and dramatic form created the great episodic cycle of the 16th century classic Chinese novel known as “Monkey” or the His-yu-chi which amalgamated among other elements the extensive travels of Hanuman in quest of Sita. This motif enriched popular culture and folklore and also contributed to the development of Chinese secular literature.

Like the Indian Suryvamsha, the Sun is a symbol of the sovereign upon earth in China. The Sun is defined as corresponding to that which is solid or complete. It is a symbol of virtuous government. It is powerless when obscured by clouds: so a government is without effect if evil counsel intervenes. As Surya shines on high and low alike, the people should, similarly, be impartially treated. In the Chinese work Fo-pen-hsing-ching, which was translated from Sanskrit by Pao-yun in 427-449, it is stated that Mother Maya saw the future Buddha as an elephant entering her womb. The elephant carried on its head “the solar essence”, and the Bodhisattva riding the elephant is compared to “the luminous pearl of the sun” and Mother Maya states that “sun-light has entered her womb”. With the introduction of Buddhism into China the Surya became symbolic of nobility, purity, and light. In the cult of the Lord of Healing or Bhaisajyaguru, Suryaprabha and Chandraaprabha represent eternity of time.

In China, it was believed that the Lo-hou hsing or Rahu is an unlucky star, which tries to devour the sun at the time of eclipse. The evil spirit of this star is said to have retarded the birth of Sakyamuni Buddha for six years. The temple drums and gongs are loudly beaten and crackers exploded in China to prevent this demon from devouring the sun.

In the seventh and eighth centuries, scientific works were known as “brahmana books” in China. Books with the prefix ‘brahmana’ dealt with astronomy, calendrical science and mathematics. Unfortunates since all were subsequently lost, one cannot now estimate what they contributed. It is certain, however, that during these two centuries Indian scholars were employed in the Astronomical Bureau at the Chinese capital. Kashyapa Hsiao-Wei, who was there shortly after A.D. 650, was occupied with the improvement of the calendar, as were most of his later Indian successors. The greatest of them was Gautama Siddha who became President of the Board. It seems that these Brahmanas brought an early form of trigonometry, a technique which was then developing in their country India.

Though most of their writings failed to survive, something more should be said here of these Indian astronomers and calendar-experts of the Sui and T’ang. The story begins with the books of Brahmana astronomy such as the P’o-lo-men T’ien Wen Ching, mentioned in the Sui Shu bibliography, but long lost. These must have been circulating in about A.D. 600. During the following two centuries we meet with the names of a number of Brahmana astronomers resident at the Chinese capital.

The first was Gautam Lo, who produced two calendar systems in A.D. 697 and A.D. 698, but the greatest was Gautama Siddha who compiled the Khai-Yun Chan Ching in about A.D. 729, in which a zero symbol and other innovations appeared. It is a work of great importance, often mentioned in Chinese astronomical treatises. In any case the paradox remains that we owe to Gautama Siddha the greatest collection of ancient and medieval Chinese astronomical fragments.

The translation of the first Sanskrit sutra into Chinese is by An Shih-kao in the middle of the second century. He was a Parthian Prince turned Buddhist monk. He had abdicated the throne in favour of his uncle to take up the robes. A number of his translations survive. He founded a school of translation of Sanskrit texts into Chinese, which was hailed by the Chinese literati as “unrivalled”. Among his associates were bhikshus from Sogdiana (corresponding to modern Samarkand and Bokhara) known as Uttarapatha or “Northern India” in Chinese historical works. The name of Khang seng-hui from Sogdiana stands out as a master of Sino-Indian literature and as one who preached in South China in a systematic manner. He translated even a short Ramayana into Chinese.

Kumarjiva, born of an Indian father and a Kuchean princess, educated in Kashmir and Kashgar, was a scholar of great reputation. He reached Chang-an in 401 AD and worked till A.D. 412. He translated 106 works into Chinese. Most outstanding is his Chinese translation of the Sanskrit text entitled Saddharma-pundarika-sutra, known for short as the “Lotus Sutra”. He was one of the most outstanding stylists of Chinese prose. He is the only Indian whose Chinese diction has been hailed over the centuries by Chinese men of letters.

The lotus Sutra is at once a great work of literature and a profound religious classic, containing the core and culmination of Buddha’s ageless teaching of compassion and the way to achieve liberation from suffering. For more than fourteen hundred years, it has been a rich source of themes for art. Generations of priests, nuns, and lay believers confident in the sutra’s promise of spiritual reward for those who revere it and pay it homage have made opulent transcriptions of it, fashioned lavishly ornamented caskets for its preservation, and commissioned votive art depicting its narratives and religious teachings. The range of artistic expression inspired by the Lotus Sutra is astonishing.

China has many grottoes that rival Ajanta in their synthesis of Indian suppleness, Hellenic elegance and Chinese grace. The Yun-kang caves were excavated between 414 and 520 under Wei rulers. Fiftythree caves remain till this day and contain over fiftyone thousand statues. It is one of the largest groups of stone cave temples in China. After the first Wei capital Tatung was transferred to Loyang in 494, work commenced on Lung-men. Sculpting went on for 400 years till the Thang dynasty. It has around 1,00,000 statues; the highest is 55 feet high. It is a treasure-house of China’s heritage of sculpture.

On the ancient Han frontiers, in the vast deserts of Inner Asia lies the sandy city of Tun-huang, the ‘Blazing Beacon’. In this tiny oasis are the sacred grottos of Ch’ien Fo Tung or ‘Caves of the Thousand Buddhas’, carved into a rocky cliff rising aside a meandering rivulet. The walls of these Caves are covered by murals of surpassing beauty, with the largest array of authentic painting extending over several dynasties: a task of sixteen centuries. It has ever been the sacred oasis, one of the glories of Buddhism. A stone tablet of the Thang dynasty states that the first ‘Caves of Unequalled Height’ was constricted by an Indian monk in 366 A.D., increasing upto caves as faith continued to inspire radiant visions.

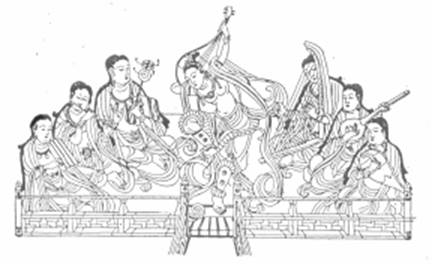

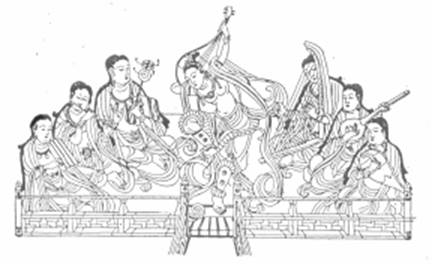

Divine musical instruments are played to which heavenly angels or apsaras

dance in Sukhavati, the resplendent Western Paradise of Amitabha. The Sukhavati

paradise has been painted all over Central Asia and East Asia, for the last two

millennia. Some of the finest murals at Tun-huang (the Ajanta

Caves of China) are of dancing goddesses

in the joyous tenderness of their vibrant movements. These dancing angels are

Indian for they were no raiments on top. Tun-huang caves show three types of

female dresses: the flowing drapery of Chinese ladies, the tight wear of Central

Asian beauties and the sensuous elegance of the bare bodies of Indian belles.

Sketch of a dancing scene in Sukhavati in

Tun-huang cave 113 of the 8-9th century

The flying Goddesses from cave 321, which belongs to the Golden Age of early Thang (618-741 A.D.) are unique. The sensuous tenderness of the body, the delicate flowing lines of drapery, the joyous colours, garments vibrating with the rhythm of space-mirror the Vigorous culture of Serindia. Bearing in their hands trays of fruits and flowers, arrested as it were in their stately flight for a moment, they seem to bid the onlooker to accompany them into worlds of luminous beauty.

Ch’an or Dhyana, was carried to China by Bodhi dharma, the youngest son of a king of Kanchi and a follower of Prajnatara’s eminent line. Palm-leaves inscribed by Prajnatara have survived in Japan. Bodhidharma reached China early in the sixth century after long peregrinations. He had an audience with the noted patron of Buddhism, Emperor Liang Wu-ti (502-550) of South China. Tradition has it that Bodhidharma crossed the Yangtze on a reed, and spent nine years in meditation in front of a rock wall at the Shao-lin monastery. Shao-lin became a centre of martial arts, where sword and Ch’an became one. Bodhidharma had said that Tao-fu had acquired the skin, the nun Tsung-ch’ih the flesh, and Tao-yu the bone, and that Hui-kho had penetrated into the marrow (the essence) of the doctrine. He transmitted the “Seal of Mind” to Hui-kho, who had cut off his arm to express the deep sincerity of his resolve. Like this statements, mist surrounds the evolution of the legend of Bodhidharma, which is as controversial as he himself must have been in life. Chan is a product of Chinese soil from the Indian seed of Enlightenment, leading to self-being.

Armies, manuscripts and scholars are allies in China. In the beginning of the seventh century after a military expedition to Champa, the Chinese army returned with booty of 1350 Buddhist manuscripts among others things. They were all of Indian origin.

With Buddhism, sugar came to China. Sugar is termed shi-mi ‘stone-honey’ in the Sui Annals which renders the Sanskrit úarkarâ from śarkara ‘granules, stonelets’. In A.D. 285, Kambuja included sugar-cane in its tribute to China. In A.D. 647, Emperor Tai-tsung sent a mission to Magadha to study the secrets of boiling sugar. This method was adopted by the sugarcane growers of Yang-chou. The official history of the Sui dynasty, completed in A.D. 610, contains a catalogue of Sanskrit works on astronomy, mathematics, calendrical methods and pharmaceutics under the generic caption of Pho-lo-men or Brahmin Books.

The earliest specimen of printing from China is a printed sheet with the figure of the Six-armed goddess Pratisara in the centre and with Sanskrit mantras in the ornamental Ranjana script, written concentrically around the figure. It is dated A.D. 757. The world’s oldest printed book dated 11 May 868 is a Buddhist work on transcendental wisdom entitled Vajracchedika, now in the British Museum. Printing flourished as an integral part of Buddhist requirements of large number of sutras and mantras for mass distribution by bereaved descendants so that deceased parents may acquire due merit. The book in Buddhism was a written medium of spans of inner space.

Sutras sanctified the state: for instance the Jen-wang-ching or Karunika-raja-sutra brought protection, peace and prosperity to the country. The collective sought its continuity in the enduring flow of Dharma. Buddhist monasteries fortified the trade caravans on the Silk Route, they ensured the flow of art and thought, and they gave rise to a Buddhist ecumene. Buddhist Central Asia and East Asia were linked in their common Dharma. When the Chinese refused aid to the prince of Tashkent in 751, the battle of the Talas River was lost. It proved to be one of the decisive battles of world history. This region, which had been a stronghold of Buddhism from its earliest times, succumbed to Islam. The contacts of China with India declined and the receptivity of China was replaced by xenophobia. In 828, Emperor Wen-tsung had an image of Avalokiteśvara set up in each of the 44, 600 monasteries of the empire. In 1950, about a million Buddhist shrines, stupas, temples and monasteries had sanctified the sprawling spaces of China.

During the Thang dynasty, Indian astronomers served on the Imperial Board for the purpose. Three Indian astronomical schools of Gautama, Kashyapa and Kumara were known at Chang-an in the seventh century. More accurate calendars were prepared anew by Indian astronomers. Sanskrit mathematical works were translated into Chinese, which are lost.

A few hundred Indian teachers went to China from the first to the twelfth century. They have bequeathed a legacy of about 3,000 works translated from Sanskrit into Chinese. We may mention a couple of them: Gunavarman a prince of Kashmir who reached Nanking in A.D. 431; Buddhabhadra, born at Nagarahara, claimed direct descent from Amritodana, the uncle of Lord Buddha. Nagarahara is modern Jalalabad. He died in China in 429. Bodhiruci was from South India. A Chinese envoy came to the Chalukya court in A.D. 692 to invite Bodhiruci. He reached China in 693 by sea and translated Sanskrit works. One of the last outstanding Indian teachers in China was Dharmadeva of Nalanda. He was received by the Chinese Emperor in 973.

The Chinese pilgrims to India like Fa-hsien, Hsuan-tsang, Wang Hsuan-tso, I-tsing, and others have bequeathed historic records which are invaluable for the understanding of the cultural and political history of India. I-tsing has left short bio-sketches of 60 eminent Chinese monks who visited India. In 964, three hundred Chinese monks started for India, to pay Imperial homage to the holy places. They set up five Chinese inscriptions at Bodhgaya. One of the inscriptions ends: “I now make use of the eulogy of the marvelous excellence of the three bodies and the sculptures that I have executed of the extraordinary acts of the thousand Buddhas, in order to secure the prosperity of the glorious sovereign of my country and to offer to him for many years a holy longevity”.

Indian scholars were honoured guests as late as the Ming. Pandita Sahajashri led a twelve-member Indian Buddhist delegation to China. He was received by the Yuan and Ming emperors in 1364 and 1371. He was from a kshatriya family of Kapilavastu. His status and privilege placed him in a position to soften the autocratic temper of the emperor. Recently a blue and white jar of the Xuande period (1426-1435) has been discovered with Sanskrit mantras all around: diva svasti svasti madhyandine … It seeks good fortune by day, by midday, by night: at all times.

The serious study of Sino-Indian contacts began, strangely enough, with French thinkers. Voltaire admired the political organisation of China and her ethics based on Reason. He found in China a great civilisation, which owed nothing to the Greco-Roman or Christian tradition. The Chinese managed their affairs of state more rationally and without Christianity. The German philosopher Leibnitz too established the Berlin Academy to open up interchange of civilisation between Europe and China. The more the Europeans investigated China the more they found India to be the crucial roots, in fact the Greece of Asia, the birthplace of philosophical ideas and the overwhelming influence in art and poetry.

The chinoiserie of the 18th century led to revealing the fabulous bonds of China with India. In their study of China, freanch scholars started to unravel Central Asia and India. Jean Pierre Abel-Remusat published a history of Khotan in 1820 and his French translation of the travels of Fa-hian through Central Asia, Afghanistan and India appeared posthumously in 1836. By his labours, it became evident that Chinese sources were fundamental to the understanding of Indian history. In fact the Indian pronunciation of this first great Chinese pilgrim derivers from Abel-Remusat’s transcription, like that of his illustrious successor Hiouen-thsang. The travels and biography of the latter were again translated by a French scholar, Stanislas Julien in 1853-58. The biography of Hiouen-thsang after his return to China, as summarised by Julien, is still our main guide. Indian scholars rarely have access to this French work and are thus deprived of detailed knowledge of the academic achievement of Hiouen-thsang after his return home. Julien was again the first to point out that Sanskrit literature had been translated into Chinese on a gigantic scale for a thousand years. A renascent India seeks to renew her relations with Chin, with the sacred wisdom of ages, with no-mine-ness, all attribute-less and unconditioned.

The long and time-honoured contacts have been mature time, reverberating in a subtle interweave of thought, ritual, legend and art. They are symbolic of the deep of the heart that has never been too subtle for habitation. A Chinese poem written for me speaks of the new moon, the flowing clouds, the drizzling rains and the blooming white lotus at one go. The White Lotus is Buddhism, which is inextricably interwoven with the woods, lakes, mountains and warm hearts of India and China.

India and Japan: Interflow of Culture

A poem of a thousand years ago in the Kokinshu became the national anthem Kimigayo in the last century. Its lines have wrought magic of such magnitude and consequence in the mind of Japan that we can only wonder in silence:

Rule on, my lord, till what are pebbles now

By age united, to mighty rocks shall grow.

While the inner bastions of Japan endure in their creative majesty, the path she has trod to civilisation of modern science and technology is a miracle. Japan is a wonder of non-Euclidean economy: the words of Kimigayo have become a reality: tiny pebbles have grown into mighty rocks.

The cultural harmony of India and Japan goes back to AD 552 when the first Buddhist teachers arrived with sutras and statues. Couple of decades later Prince Shôtoku spread the splendour of Buddhism in the land of the Rising Sun. Japan emerged from the limbo of her prehistory, under her Ashoka, Prince Shôtoku (AD 574-621) who drew up her first Constitution, wherein the Triratna (Buddha, Dharma and Sangha) were a fundamental factor. He constructed several Buddhist monasteries. Among them the Horyuji “The Temple for the Flourishing of Dharma” (Dharma-varshana-vihara) near the city of Nara is the most ancient wooden building in the world.

The kond"o or golden hall of the Horyuji is adorned with murals, whose style has close affinities to that of India. It reflects the artistic achievements of the seventh century. In the years AD 643-646, 648-649, and 657-661 the entourage of the Chinese envoy Wang Hsüan-ts’e copied the frescoes on the walls of monasteries in India. Later on these paintings were compiled in 40 fascicules. Some of them were taken to Japan by the Korean artist Honjitsu, and they became the models for Horyuji murals. The Buddhas and Bodhisattvas of Horyuji, with a rich dark patina of centuries, evince a particular purity of line, surface and decoration and desire to see humanity, flesh and blood, fused in most abstract of deities. The Horyuji monastery has yielded one of the most ancient Sanskrit manuscripts of the Usn+isavijay"a-dh"ara{n+i in the Gupta script.

The v+in"a under its Japanese form biwa is as integral characteristic of the Japanese Sarasvat+i. The most ancient biwa known today is preserved in the Sh"os"oin Repository, dating to AD 757.

In AD 799 an Indian was washed ashore somewhere in the Mikawa province. A young man of twenty years, with nothing to cover his body except a straw coat and short drawers, he was stranded in a country where none understood him. Years later when he became conversant with Japanese he said that he had come form India. He had seeds of cotton with him. He lived at the Kawadera temple at Nara. Two ancient chronicles Nihon-koki and Ruiju-kokushi mention that he introduced the cultivation of cotton which became the most important clothing material. The Japanese words wata or hata for cotton are derived from Sanskrit pata ĽiV˝ .

With the advent of the ninth century, Japanese life had been transformed by assimilation with Buddhist civilisation. The blossoming of the great continental culture in insular surroundings reached its culmination in the personality of Kobo Daishi (AD 774-835), who visited China to drink at the purest springs of Dharma. Kobo Daishi’s new denomination of Shingon or Mantrayâna was a new moral conscience of the country. He proclaimed Buddhahood to be the potential privilege of all as against the predestined few. He became an outstanding genius in Japan’s cultural evolution. For the first time he founded a school for the children of common people. Till then the academies were open only to children of families above the fifth rank. To achieve this historic democratization, he created the Japanese kana syllabary of fifty sound: a i u e o, ka ki ku ke ko, etc. based on his study of the Sanskrit alphabet. The Hiragana alphabet was the cursive form, which was woven into the Iroha poem wherein the complete alphabet of 50 letters was included, and each letter occurred only once — it was a literary marvel. This poem of the alphabet speaks of the gleaming colours that blow away, the deep mountains of ephemeral life, shallow dreams, and the crossing over them all. One of the greatest poems in the Japanese language, it was inspired by the Sanskrit work Mahaparinirvana-sutra. To this day, every Japanese child begins his education with this Iroha poem.

The letter shapes reflect the spans of inner space. Thus the script used for the mantras was not purely a writing system, but a visual medium of an intrinsic dimension. Kobo Daishi was introduced by the Kashmiri Prâjńa to the Nagari script of the period, which has been designated by the Japanese tradition as Shittan, from the Sanskrit word Siddham written at the head of the alphabet for an auspicious beginning. To this day, the Japanese write mantras in artistic Siddham.

The Japanese language is written in the kana syllabary with kanji or Chinese characters. The kanji unites India and Japan at the deepest levels. All the sutras of Japan are written in kanji. The ideographic world of kanji induces a sense of discipline, dedicated work and miniaturisation by the tens of strokes in a character, their fixed sequence, and the organic beauty of the whole. It is a feeling for strokes, lines and squares. The square stones set in a carpet of moss awaiting the bare feet of a goddess. Ideogram is the living tissue of Japanese life. Our vital bonds are as eternal as the kanji.

Near Kyoto is the Golden Pavilion (Kinkakuji) which was the hermitage of Ashikaga Shogun Yoshimitsu as a Zen monk. It is a picturesque pavilion sitting in the pond, lending grace to the garden of Rokuonji temple. Here arises the ethereal pavilion of nirv"a{na overlooking the ocean of existence (bhava-sâgara). It recalls the Golden Temple of Amritsar in the centre of the pond, which is the emergence of Brahmâ from the primal waters.

The wonderful art of Ikebana, which means putting living plants in water is to love flowers as living beings and to tend them with kind feelings. The Japanese bow before the flowers after they have arranged them. An aesthetic creation is the essence of life itself. It is pervaded by the warmth of the human heart, whereby one gives expression to the universal heart. Japanese tradition speaks of “Indian monks who, in their universal love were the first to pick up plants injured by the storm or parched by the heat, in order to tend them with compassion and endeavour to keep them alive”.

The roundish Daruma doll is a must for success in life. You buy it, eyes are blank, you paint one pupil before embarking on a project (can well be an Election!), and if all ends well, the second pupil is added, and Daruma is rewarded by full sight. The Daruma doll is the Indian âcârya Bodhidharma, the founder of Zen Buddhism. He spent eight years in uninterrupted meditation. At last when he tried to stand up, he found that his legs had atrophied. Thus the ancient frontiers of the collective mind live on.

The leading Japanese cultural historian Prof. Hajime Nakamura says: “most of the Japanese regard India as their spiritual motherland”.

Japan is a world that is astonishing in its unity and continuity – spanning fourteen centuries. A Beauty, both sublunary and celestial, human and divine. The world of imagery still flows into the stream of life in Japan.

For the centuries of India is an aching overflow of silence. Today, Japan is the shloka, the ecstasy that emerges from this shoka, this agony, as did the muse of V"alm+iki. The Epic poet of India V"alm+iki burst into a metrical shloka grieved (shoka) at the sight of a love-lorn bird-couple shot by a hunter. Likewisae, our silence of history should become the scintillation of a new future. We look up to Japan in wonder and awe, as inspiration and creative catalyst, as dream and doing.

India and Japan:A Cultural Symphony

The vast Japanese world is referred to as karyu-kai, that is, ‘the world of flowers and willows’. It is the world of fleeting illusion, an expression rooted in Japan through Buddhism, wherein transience is the nature of things phenomenal, like ‘the perfume of a flower pressed between the pages of a forgotten book’.

The famous gigantic Buddha, the Daibutsu of Nara, symbol of the immensity of life (prano vai virat), represents Vairochana the effulgent illumination. When it was installed at Nara in the eighth century, its consecration (pranapratistha) was performed by the Indian teacher Bodhisena. Bodhisena also introduced court dance and music (bugaku) from India. Bugaku is a unique cultural asset of Japan and the Japanese are proud of this art. Careful attention is paid to its preservation by the imperial household. It is still performed at national celebrations and in honour of visiting dignitaries.

The universe itself is the body of the supreme Buddha, Vairochana

To lay the foundations of Mantrayana, Kobo Diashi visited China to study the transcendental path under Hui-kuo ( 746-805). He was initiated by Hui-kuo into Tanric sutras and their pictorial representation in the form of mahakaruna and vajradhatu mandalas, known as the Genzu mandara or twin mandalas. These mandalas synthesize the transmission by Subhakara-simha of Nalanda and Vajrabodhi of Kanchipuram. Through Hui-kuo, who was a direct disciple of Amonghavajra, Kobo Daishi inherited the Tantric tradition of Amoghavajra (705-774) “the master of eloquence and wide wisdom”, whose genius was responsible for the Chinese translation of the Vajradhatu-kalpa on the contemplative system of esoteric yoga, which was visualized in the painting of the twin mandalas.

The twin mandalas represent innate reason and primal enlightenment, harmonizing in compassion and dynamis. Herein the sadhaka identifies himself with the forces that govern the universe and collects their powers within himself. The light that burns within spreads out and is difused, guiding him towards noble paths. The iconic manifestation of the Unmanifested leads to the luminosity of Consciousness.

The pair of mandalas is the origin of the Buddhas, and of the body and mind of sentient beings. The great classical Japanese commentary Hizoki says that the mandalas are the dharma of the Buddha transmitted esoterically. It cannot be expressed in words. So it is manifested. It cannot be expressed in words. So it is manifested to the yogin in illustrations.

In 806 Kobo Daishi returned to Japan with profound gods born unto him, with homa consuming baser passions, his total being illumined by a new vision, as he carried the sutras expounding the Vajradhatu, as well as its pictorial representation in the form of the twin mandalas.

Hui-kuo, the guru of Kobo Daishi, had the twin mandalas drawn for him in accordance with Tattva-sangraha, by the famous printer Li-chen assisted by more than ten other artists. They were polychrome. They found full efflorescence and fruition in their new milieu. The original paintings of the mandalas brought by Kobo Daishi are now lost, but from them were painted the Takao mandalas in 824 in gold and silver lines on purple damask silk in polychrome. These are now preserved at the Jingoji monastery.

The Toji monastery has also preserved a multicoloured painting of the two mandalas, painted by a monk-master from the original mandalas brought from China by Kobo Daishi.

The Takao and Toji mandalas, along with the Kojima mandalas (mid-Heian period), constitute the three fundamental versions of the twin mandalas. The Kojima pair were drawn in golden lines on purple damask silk in the eleventh century. They have been handed down to the Kojima monastery.

In the twin mandalas is mirrored the realm of Shingon or Mantrayana infused with Hindu deities. It is a complex empyrean populated with gods and rishis, spirits and furies, ‘the inexhaustible beauties, potentialities, activities and mysteries of the world’ transformed into celestial personages. Here is the deep link of mantra with the arts: by sacred gestures (mudra), wealth of symbolism, liturgy, music, incense and song we return to art.

The Mahakaruna mandala is illustrated on the opposite page in the wood-printed version of Buzanji. In its outermost quarter of vajras we find the representation of sages (rishis) like Vasishtha or Basusen in Japanese, Angiras and Atri, masters of the ‘ornate heart of mystery’.

In the realm of the indestructible diamond of ultimate truth, we find the Japanese form of Bon-ten or Brahma with his four faces.

Racing on fiery steeds is Aditya or Nitten.

Shiva and Parvati or Uma and Maheshvara are known as Umahi and Daijizai-ten in Japanese. How very Japanese they are, in their blod and charming strokes. Parvati has her hair tied back like a daughter of Japan with the perfume of the earth still lingering about her.

Vishnu in its simple Japanese grace is a rhythm emerging subtly as a secret conveyed by the purity of line in unfilled spaces.

Saraswati or Benzaiten appears with a biwa, sprung from the very soil of Japan. The Japanese representations of the gods express a deep respect for the dignity of the human form, a love of purity and a vivid feeling for man. According to a Japanese text: “Saraswati is the compassionate mother of all sentient beings. Her virtuous merits pervade the three thousand worlds. She bestows treasures. She is wondrous wisdom. She grants longevity and happiness. As she presides over music and eloquence, she is also called ‘beautiful-sound devi’. As she is a goddess of profit, virtues and knowledge, she is also known as ‘guna-devi’. She grants desires to those who pray for treasures or profit, eloquence or music dexterity or wisdom.”

Even Ganapati or Vinayaka found a place in the Shingon pantheon, lording over categories (gana) as the Cosmic Person. The elephant-headed man, as Ganapati is, expresses the unity of man, the microcosm, with the Great Being, the Macrocosm, pictured as an elephant. The Japanese names of Ganapati are Binayaka, Shoden and Kangiten. Binayaka is the most usual application in the Hizoki. Kangiten denotes the god of happiness, prosperity, and well-being. Shoden can be rendered into Sanskrit as Aryadeva.

Besides, specific manifestations have individual names. There is a lovely illustration of this Ganapati with an axe and a radish in a ninth century scroll, kept in the Daigoji monastery at Kyoto, drawn in 821 A.D.

In Japanese worship, mudras are an integral part to evoke the visual presence of divine epiphanies in the mind of the initiate to transform his inner being. Ganapati is represented by two mudras in the popular mudra manual for worship.

Ganapati is still worshipped in Japan. At the Jingoji monastery of Takao, a special temple is consecrated to the esoteric twin Ganapati and every year worship is held in his honour. In other Mantrayanic monasteries too special shrines are dedicated to Ganapati. Homes in Koyasan are hallowed by Ganapati.

On the last day of my stay at Koyasan, I sat on a bench waiting for the bus to the railway station. Curiosity took me inside a shop nearby and there was a graceful image of a standing Ganapati in white wood. My repeated entreaties to the shop-owner to give it to me only evoked smiles and polite bowings. Alas for my vain desire! The overflowing bounty of the grace of Ganapati still glimmers in the adoring hearts of Japan.

About 900 deities of Indian origin are represented in the cosmographic art of Japan, representing abstractions of thought and intensity of life, the abstruse and recondite Mikkyo or esoteric doctrine around Vairochana, ‘the great light.’ The universe itself is the body of the supreme Buddha, Vairochana. This great art is koreru ongaku or ‘forzen music’ of manifest forms, awaiting one who has attained the summit, the himitsu shogon shin or the “ornate heart of mystery.”

In the graceful line and colour of Japanese paintings over the centuries the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, devas and dharmarajas grahas and nakshatras, rashi and rishis gleam in aspects that range from serene enlightenment to ferocious combat with forces of evil and ignorance. Here the Japanese painter or sculptor has concentrated his efforts in expressing in human terms a calm exterior and an intense introspection. The multiplicity of arms and leads is resolved into the rhythm of form. Here is the world of Indo-Japanese art which, in the words of an eighth century inscription,

Calms us, gives us a tranquil mind,

Every vulgar shadow is dissipated,

And caprice is subdued.

Joy, yes, and Harmony.

The woodcut iconography of

Indo-Japanese art has been reproduced by Dr. Lokesh Chandra in his maxi-volume

The Esoteric Iconography of Japanese Mandalas. The woodcuts go back to

the Takao mandalas of 824 AD through Ken-i’s monochrome copy drawn in

1035 A.D. on the 200th anniversary

of the nirvana of Kobo Daishi. It is highly educative to present some of

them.

Manjushri Bodhisattva (Jap. Monju Chintamani or “The wish-granting

Bosatsu) in the five-storeyed Pagoda of jewel” from the Toji monastery at

the Horyuji Temple, radiating spiritual Kyoto. It is the emblem of the

beatitude. 7th century. Bodhisattva’s power of salvation.

Shubhakara-simha, an Acharya of the Nalanda University in the 8th century, as depicted at the end of the manuscript entitled Gobu-Shingan or Rita-samhara in 1171 A.D.

Page of a Sanskrit manuscript preserved at the Reihokan Museum, Koyasan. 8th century.

Vasistha from the Japanese woodcuts going back to Ken-i’s monochrome copy of 1035 A.D. Vasistha is known in Japanese as Basusen.

The rishis Angiras and Atri are accompanied by their consorts. 1035 A.D.

The Chaturmukha (four-faced) Brahma is called Bon-ten in Japanese. He appears among the Twelve Devas. 11th century.

Shiva and Parvati, both riding on the bull, in the tradition of Shingon. 11th century (Ken-i’s drawing).

India and Korea:

Some events are the mile-stones in India’s historic, cultural and religious links with Korea.

Princess of Ayodhya. (AD 42); Kingdom (42-532 AD); (defeated by Shilla)

The confluence of India and Korea for the last two millennia is fine and firm, “a stone niche woven like silk”, a song, a sky, a spring, the caress of a keen coming together. It prompts a journey to an interior that we can never leave, the light of Dharma’s eyes. Our journey begins in the rocky remains of two thousand years ago when Korea, the Land of Morning calm, found its identity, its self-being in a new syndrome. A Princess of Ayodhya arrived from India to Korea in AD 48 at Kimhae aboard a ship, with the Three Treasures of statues, sűtras and úramanas (monks). She became the Queen of the founder of the first Korean state of Karak. She established the first national capital and named it Gaya. From a tribal order Korea emerged as a state. This momentous event hovers silence captured in a photograph in the exhibition. Its spirit and beauty are visit in the sportive play of nature and the simple subtlety of the heart. In gratitude to the Sea that allowed safe passage to the Queen to his shores, the King built the Haeunsa ‘Temple of Sea Grace’ that stands to this day near the top of Punsongsan Mountain.

Rocks and ruins strewn around Kimhae are the proud heirs of the cultural legacy of the Princess of Ayodhyâ from India, the Queen of the first Korean King. Heeding a call from Heaven, she sailed from India to Korea enduring hardships and high waters. She became the Queen of King Kim Suro-wang. A powerful kingdom with a highly developed culture arose in AD 42 and continued till its demise by Shilla in AD 532. Hoehyon-dong, the city of the tombs of the King and Queen, is conserved as a Historic Site by the Government of Korea.

Koguryo (372 AD); Master Mallananda (384 AD0)

Buddhism was officially introduced into Korea during the period of the Three Kingdoms: Koguryo received it in 372, Paekche in 384, and Silla in 527. It was the Indian Master Mallânanda who brought Buddhism to Paekche in 384. It gave the Three Kingdoms a new meaning: they became civilisation. In its first energy and freshness, it filled the country with benefits, nourished art, diffused education, made roads, established resting places, promoted beneficence and multiplied comforts in a thousand forms. It was a humane system of morals and of aspirations to nobility. It made vivid and tangible the presence of a profound social and cultural order.

Hwarang (520 AD)

Mirmk or Maitreya in a pose of profound thought. The earliest image is dated to AD 520. It is a thinking or pondering image with teacher Maitreya seeking a forceful point to make, measuring every idea and every word to make it a compelling logical argument, to make it a battering ram. At the same time, in keeping with the yogâcâra emphasis on dhyâna, the overall impression of the image is pensive. This Maitreya was associated with the fraternity of young Korean warriors known as hwarang ‘Perfumed Followers of the Dragon Flower’. They had enormous importance during the Three Kingdoms and Unified Silla Dynasty. Their five principles were: (i) to serve the state with loyal heart, (ii) to give filial respect to one’s parents, (ii) share with one’s friends a sincere affection, (iv) to fight without retreating, and (v) never to take life without purpose. SOn (Zen) and sword are one: bhakti is transitive to shakti.

Pulguksa (535 AD)

In 535 the first great cathedral of Buddhism was founded and called Pulguksa. It is the oldest surviving Buddhist monastery of Korea. It means: pul ‘Buddha’, guk ‘land’, sa ‘monastery’, a monastery that springs from the deeps of Buddhism, to celebrate the new dynamic and vital order that was to determine the tonality of Korean life for centuries. The most skilled workmen were summoned to make it a monument of restrained dignity and quiet peace.

King Munmu (661-681)

The first rays of the rising Sun have touched the forehead-jewel of the Buddha, which in turn has cast its sheen on the waters of the eastern Seas, exactly on the spot where King Munmu (who ruled during 661-681) sleeps in eternity. He unified the Three Kingdoms of Korea into One state. In gratitude, he ordered the construction of the Temple on the shores of the eastern Sea to safeguard the new State. The King envisioned the transcendental Rochana Buddha to cast his rays for ever, over the web of power in the fabric of society, in the subsuming unity of his Land. Ever since colossal Buddha touching the earth, has been the dynamic symbol of unity, interwoven with the language of real life.

Yi-do Script (late 7th century)

In the latter part of the seventh century Shul-ch’ong invented the Yi-do script to denote case-endings in the margin of Chinese texts. It was to aid the reader in Koreanising the system of the Chinese sentence. At first he composed eight case-endings, that is, nominative, accusative, intrumental, dative, ablative, genitive, locative, and vocative. He probably based them on the Sanskrit case-endings. His father was a great Buddhist scholar, and he must have taken his help. The book Kyun yu Chun, written in 1075 AD. says: “The Yi-do resembles the Sanskrit in its inflections”. In 1446 the sage-like emperor Seijong invented a new Korean alphabet and moveable printing types. This alphabet continues to this day as the Han-keul or “Proper Writing”. Dr. Kei Won Chung in his dissertation to the Princeton University says that the Korean alphabet was composed on the principle of the Sanskrit alphabet. With the new alphabet, learning became accessible to a large mass of people.

The pensive images of Maitreya are coaeval with the period of the consolidation of the Korean state. Maitreya cult was practised at the Silla court by young aristocratic warriors who formed a fraternity known as the Hwarang ‘Perfumed Followers of the Dragaon Flower’. This name is an allusion to the nâgapu{spa tree under which Maitreya Bodhisattva will become a Buddha. They had an enormous importance in the government both during the Three Kingdoms and Unified Silla dynasty. They were responsible for national unity. The Buddhist kingdom of Silla accomplished the unification of the Three Kingdoms and formed the nation-state of Korea for the first time in history. Ever since, Korean Buddhism was the destiny and defence of the land. Monk Wolkwang formulated the “Five Worldly Commandments” to form the basis of a national ethos.

Hyecho returned to Korea (&27 AD)

The Korean Hyecho became a disciple of the Indian teacher Vajrabodhi as a youth of sixteen years. Later, he travelled to India by the sea route and returned in December 727 via Central Asia. In Samarkand he records one Buddhist monastery with one monk. Hyecho is the last pilgrim on the historic Sutra Route, before the monasteries and monks perished in the onslaught. He records this wounded time in his Travel Records which are on par with those of his celebrated predecessor Hsüan-tsang.

The great Korean pilgrim to India, Hyecho translated a hymn to the Thousand-bowl Manjusri in AD. 741. It is still available and is one of the rare works of Korean scholarship accorded the honour of being canonised in the Buddhist Tripitaka. Buddhism contributed to the evolution of Korean literature, specially in prose. The Buddhist works were based on stories from the Buddhist canon. They were not merely translations but often new writings. Their tone is devotional, and in a strange way elusive. Their language is both rich and direct. Their poems are inspired, and their narratives are interesting and detailed.

Sokkur-am (742 AD)

The legends and history of the Three Kingdoms of ancient Korea, Samguk yusa, written by the Buddhist monk Ilyon (1206-1289) gives accounts of the foundation of Buddhist temples and pagodas. In its chapter on filial piety, it narrates how Kim Tae-sOng, the prime minister of King KyOngdOk commenced the construction of SOkkur-am in A.D. 742, and repairs of and additions to the Pulguk-sa monastery which was founded in about A.D. 535:

“His heart moved by heavenly grace, Kim Tae-sOng built the beautiful Pulguk Temple in memory of his two sets of parents and also founded the wonderful grotto of SOkkul-am. He invited the two distinguished monks Sillim and P’yohun to supervise these temples. He had his fathers and mothers represented among the images in these temples in gratitude for bringing him up as a useful man.

“After the great stone Buddha for SOkkul-am was finished, Kim Tae-sOng was working on the lotus pedestal when suddenly it broke into three pieces. He wept bitterly over this, and at length fell into a trance. During the night gods and goddesses came and helped. It is a pearl of East Asian cave temples in its overall planning. It enshrines the best Korean sculptures of all times. They are reminiscent of the sculptural glories of T’ang China, and yet are unique in their ethereal quality. Superb examples of warm naturalism inspite of the hard medium of stone, they remain unsurpassed in East Asian lands. They sprout from the passion of everything that the eyes embraced, celebrating its essence in the eternity of stones:

“There is a tradition that the sculptor who carved these bas-reliefs was in love with the King’s daughter and used her as the model for the image of Kwanum (Avalokiteśvara) in order to immortalize her beauty”. (Ha 1972: 386 n. 4)

The piety of the patron and the tender love of the sculptor sinks into the silent rapture of these live sculptures in their kissed limbs, smiling in flowing drapery and deep solitude.

Childs’s prayer (742-765 AD)

Three in the morning, the monk in charge of the morning chanting sounds the wooden mokt’ak to awaken the sleeping temple. A magnificent zinnia rustles in the garden as if it were rubbing sleep from its eyes. As he circles the temple compound, he recites a soothing chant, that flows smooth as water. The chant is a stotra of Nîlakantha, represented as Kwanum with a thousand eyes on a thousand hands.

The Samguk-yusa records a hymn sung by a country woman named Huimyong who lived in the time of the Silla King Kyongdok (r. 742-765). Huimyong’s child was blinded at the age of five. She took the child to a temple and sang the following to the Thousand-eyed Kwanum, painted on its north wall.

I fall on my knees and implore you

Thousand-eyed Bodhisattva.

You have so many eyes,

Can you not spare two for my child?

Your compassion is so great.

And with this song, her child’s sight was restored.

Emille Bell (771 AD)

The largest bronze bell of Korea, weighing 25 tons, was completed in AD 771 during the reign of King Hyekong. After years of repeated failures, the sculptor could cast it to perfection only by throwing his beloved little daughter into molten bronze as a sacrifice. The lingering tone of the bell suggests the cry of emille ‘mother’, the sad, helpless wails of the little girl. It is often called the Emille Bell. Her heart-rending cries are eternalized in the peals of the bell. She is the tiny pilgrim to the yonder shore, the pâramitâ beyond samsâra, ferried away in the vanishing ring of the colossal bell:

I am a ferry boat.

You’re my passenger.

She is in the land of Nowhere, as the Korean monk sings to the receding chimes of the bell:

gate gate pâragate pârasamgate bodhi svâhâ

xrs xrs ikjxrs ikjlaxrs cksf/k Lokgk

Tripitaka Koreana at Haein-sa (1251 AD) - 81,258 blocks

To ward off the Mongol invasion, the king of Korea had 81,258 wooden blocks of the Tripitaka Koreana engraved. Completed in AD 1251, they have been preserved in perfect condition to this day at the Haeinsa monastery on Mount Gaya. They reflect the glory of national unity. Befitting its reputation as a Sűtra-Vihâra, Haeinsa is the foremost meditation centre of the Chogye sect. Stillness reigns where monks meditate to encounter their inner self. As the evening mist pervades the valleys, and mountains dull into darkness, the windows of the monastery are lit one by one by monks preparing to cross over the 108 passions to the sea of Buddha’s wisdom. The Korean Tripitaka done for the defence of the country, is marvel of Korean technology seven centuries ago. It is important for the excellence of its editing and for its beautiful block-printing.

Dhyanabhadra (1326 AD)

The last Indian Acharya to visit Korea was Chikong (Dhyânabhadra). He arrived in Korea in the 1340s and established the Juniper Rock Monastery on the pattern of the Nalanda University. Its foundations can be seen near Seoul. He wrote Sanskrit dhâranî-mantras on the gigantic Yonboksa Bell for the liberation and peace of the Korean people from Mongol domination. An inscription at the Juniper Rock Monastery dated 1378 records the life and work of Dhyânabhadra and informs us that the king of Kanchi was his nephew. The mill for making sattu installed by Dhyânabhadra still lies at the site of this Monastery.

Seoul has the only Buddhist Broadcasting Station in the world: it exalts the glory of Korea’s identity. A restaurant called “Perfume of Grasses” recalls the cuisine of Acharya Dhyânabhadra. It serves “tea of honey-stick”. Honey-stick is liquorice e/kq;f"V Ľeqys Bh in Hindi˝-

General view of the foundations of the Juniper Rock Monastery.

It was built by Chikong, modelled after the Nalanda University of India. It was the biggest monastery in Korea with 268 rooms, with an area of 33,000 sq. meters. More than 3,000 monks stayed here until the beginning of the Chosun Dynasty. The Monastery was destroyed by fire due to Chosun Dynasty’s policy of the repression of Buddhism.

Muhak, a disciple of Dhyanabhadra, Seoul (1327-1405 AD)

Portrait of Muhak (AD 1327-1405), a disciple of Chikong. He met Chikong in China in AD 1353, who recognized that Muhak had perceived the doctrine of Buddhism. He played a historic role by suggesting to the Founder King of Chosun Dynasty to move that national capital from Kaesung to Seoul.

Sage Emperor Seijong (1446 AD), Invention of Hangul

In 1446 the sage-like emperor Seijong invented a new Korean alphabet and moveable printing types. This alphabet continues to this day as the Hangul or “Proper Writing’. Dr. Kei Won Chung in his dissertation to the Princeton University says that the Korean alphabet was composed on the principles of the Sanskrit alphabet. With the new alphabet, learning became accessible to a large mass of people.

Colossus of Maitreya (1991 AD)

In 1991, Korea dedicated the world’s largest bronze image Maitreya at Popchusa monastery. This 100 feet high statue embodies the aspirations of the Korean people for national re-unification. The Popchusa was built in 553. Two centuries later, in 776, monk Yulsa erected a 40 feet gilt bronze Maitreya for national prosperity and unity of the people. During the Eye-Opening Ceremony in April 1991, three rainbows appeared in the clear sky: “Isn’t this a sign that we can even move heaven when we are truly devoted? When we build an image of Maitreya in our hearts too, all lives on earth will turn into lotus flowers, and the very world around us will become a pond of joy” (Chief Abbot Yu).

I Do Not Know

Whose footprint is that paulownia leaf

that drops softly, rousing ripples in the windless air?

Whose face is that blue sky

glimpsed between the dark, threatening clouds

blown by the west wind following a long rain?

Whose breath is that fragrance in the sky

over the flowerless tree, over the dilapidated tower?

Whose song is that bickering stream

that quietly flows, starting from nowhere

and making the stones moan?

Whose poem is that evening glow

that adorns the waning day,

its lotus feet on the boundless sea,

its jade hands patting the sky?

Burnt ash becomes fuel again.

My endlessly burning heart!

Whose night does this flickering lamp illumine?

Ż A poem by Han Yong-un (1879-1944)

one of Korea’s greatest poet, patriot, monk

who played a major role in the independence movement.

Han’s motherland was human love and ultimate being

in the enigmatic SOn (Zen) language of Paradox and irony.