Dialogue April-June, 2015, Volume 16 No. 4

Whither Goes Af-Pak Post-2014 Drawdown?

Ambrish Dhaka*

Introduction

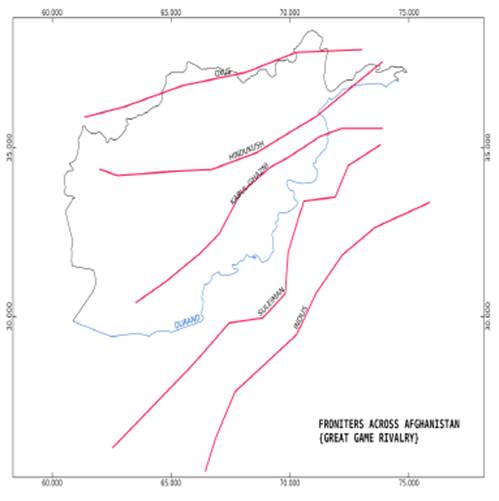

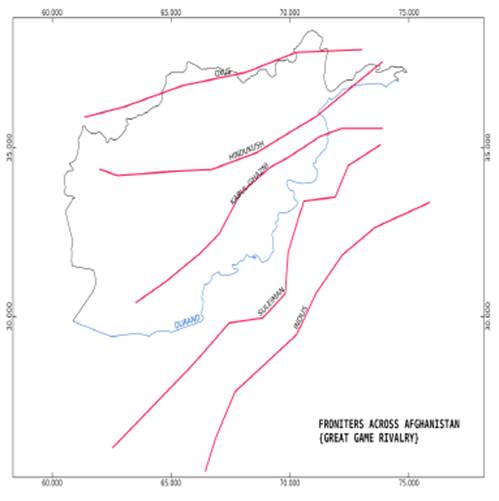

The Af-Pak border of Durand Line has become more a symbol of body politic defying the corpus of State on either side by disenchanted Pashtuns who would commit violation of State law and cross over to the other side at will. The act that has had always brought the sovereignty of State to a naught, where violation seems the only possible way of nabbing the culprits. The questions of territoriality and borders have plagued Afghanistan and Pakistan in post-colonial times. The tribes have used mountainous terrain and porous border to defy the State and also change the narratives in favour of the host State that is used to strategic shelter. The notion of strategic depth no longer remains a State narrative so far as Pakistan and Afghanistan are concerned. The strategic depth has already been practised for more than a century by Pashtuns residing along Durand Line, whenever there arose a need to escape from State hostility. The Pashtun tribal groups do not raise arms against any of the States, but their mere sign of non-cooperation in security measures is a sufficient bargaining chip for all that is held high in reference to their honour, which might even mean implicit freedoms. There is a absorbing account given by Akbar Ahmed in his book, The Thistle and the Drone of a rebel leader, Safar Khan, who almost emulated Osama bin Laden of his times, but with negotiations and guarantees of fairness in trial finally acceded to surrender.1 The problem of security remains a multi-tiered problem that plagues not inter-tribal relations but also affects inter-State relations. There is also cognition of the fact that States do get involved into tribal affairs that has the potential of larger order destabilisations. Amid this there is the presence of the US with its drone warfare conditioning the border areas with personality strikes. These personality strikes also hit at the social space that gets enmeshed into data. The kinsmen killed further make the ground situation virulent creating a bleak chance for settled borders. The effort to convert Durand Line a hard border has been a constant failure even in the aftermath of 9/11. The post-9/11 situation induced the issue of Taliban’s cross-border movements for attacking ISAF & NATO forces that have complicated the border issue. The accusation of harbouring each other’s adversary lends territoriality into problematic sphere. There have been failed attempts to fence the rugged mountainous terrain and also install biometric system at Chaman, but Afghans have opposed these to the extent of rendering them dysfunctional.2 The major problem remains on the account of twin focus on border and the territoriality on Pakistan side. The Pashtun population on the Pakistani side has largely remained outside State’s influence. Afghanistan has contested Pakistan’s inheritance of those territories as were annexed by the British in the aftermath of the Second Anglo-Afghan War. The historic legacy of conflict has prevented formalisation of Durand Line as mutually accepted border for long. The making of Durand Line involved lot of give and take. It allowed Dir, Swat and Chitral under the British possession, and similarly Waziristan was also under the British. But, the Afghan Amir secured possession of Birmal district of Waziristan and Asmar district of Konar Province as strategic access to Nuristan province.3 These localised geopolitical considerations made permanent case for destabilisations along Durand Line. The idea could have been none else than the culmination of the Great Game rivalry that essentially saw frontier as divisive geographical feature rather than an amalgamate of fading limits of empires. The replete production of such divisive lines gave geopolitical scars on Afghanistan with none the less five frontiers of which the Durand was the deepest and the middle most one, as evident from the figure 1, below. The five frontiers from south to north are, 1) Indus river, 2) Suleiman mountain foothills, 3) Kabul-Ghazni-Kandahar highway, 4) Hindukush mountains, and 5) Amudarya (Oxus) river.

Figure 1. Frontier zonation of Afghanistan as a result of Anglo-Russian rivalry:

The Forward Policy school in the aftermath of the Second Anglo-Afghan War decided to demarcate the northern borders of Afghanistan and as a result it was the Afghan-Russian border that came first and Durand Line was the last one to emerge.4

The Elusive Peace

Afghanistan is seen as the land for geopolitical buzkashi. This trepidation of external powers playing partisan in domestic politics of Afghans has always hounded out any chance of peaceful development with the region. The latest binary narrative being dished out in the form of India-Pakistan competing out each other has further linked the bilateral issues of concern, such as, the Kashmir insurgency. The security of Afghanistan emanates from larger order within South Asian Regional Security Complex. The epistemology of the concept hinges on the quest for cultural identity and their manifestation in national identity of India and Pakistan. These contested identities have their overspill in the region in dichotomous manner. The idea of a nation-State being religious has its own difficulties in reconciling with international order where there are no takers for religious Statehood. This further goes downward in emulating such uniformity under religious nationalism that hinders the segmentary spaces, which have ethnic or other kinds of geo-cultural orientations. The resistance to religious nationalism becomes a threat to State security which caters to marginalisation of groups that have potential vulnerabilities from the neighbourhood. The South Asian security complex is characterized by an array of definite issues, 1) the fear of Indian hegemony, 2) conventional and nuclear arms race, 3) Kashmir issue, 4) Siachen issue, 4) Water dispute, and 5) 26/11 terror attacks.5 The role of religious binary that rooted for partition of the communities who culturally remained inseparable as water took nationalistic turn with more and more symbols accorded to mark the distinction. The nuclear power and economic development became one of the strongest markers of distinction that no longer needed religious identity of the initial years. The nuclear bomb and the status of haves and have nots became a piquant quest between India and Pakistan, who both are non-signatory to NPT.6 The growing disparity of conventional arms and extension of deterrent architecture from land to sea-based platforms is extending the arms race from South Asian subcontinent to the Indian Ocean at large.7 The arms race has always involved major arms exporters extracting their strategic mileage from the region. The US always sought to counter USSR by supporting Pakistan during cold war period. China has acquired South Asian ambitions under the axiom of peaceful rise by providing assistance to Pakistan for its nuclear programme, weaponisation and economic infrastructure. The Pakistan-China Economic Corridor extending from Xinjiang to Gwadar has raised high hopes for Pakistan’s economy. The proposal involves construction of dry ports, rail-roadways infrastructure, metro in Lahore, and plethora of energy (conventional and renewable) power plants. The projects cost is pegged at $18 billion and Chinese have promised to provide Green Channel for quick release of funds.8 The benefits can certainly provide the game changer scenario for Pakistan.

But, the moot question lies whether Pakistan is going to partner Afghanistan in these benefits of development. The question arises in the wake when Pakistan sees north-south connection as a putative geographic opportunity to its prosperity, but at the same time sees the east-west connection, be it India or Afghanistan as strategic leverage against its both the neighbours. The denial of opportunity to Afghanistan having access to South Asian markets has been a historic tool that has been deployed whenever there was a political conundrum. The aftermath of One Unit plan in1955 witnessed the burning of Pakistan embassy in Kabul and thereafter Durand Line border faced closure from both the sides.9 This Durand Line became a strategic gateway to all the NATO supplies that passed through Khyber pass and also through Quetta-Chaman pass. The 2011 Salala incident killing 28 Pakistan soldiers by the US airstrike brought halt to these routes. This brings in the vital question of Afghan-Pakistan maintaining transit relations in the wake of their respective geopolitical pressures. The US presence in Afghanistan conditions that posture, so long there is denial of opportunity and presence of threat on the eastern side of border. This has entangled relations with Af-Pak zone seeing a geopolitical complex reined by Sino-Pak alignment facing the US-Afghan military pressures on the border. India has evaded its infusion into Af-Pak entanglements by looking towards Iran for all-time land access to Afghanistan and Central Asia. This is further co-factored into north-south corridor linking Russia and Europe.

The push-pin however remains with larger handling of threats from religious extremism that has particular focus on hitting areas and symbols of development. The 26/11 Mumbai attack signified that economic institutions and development projects would be the target of jihadists who would spare no opportunity to derail these mega-transnational projects. Therefore, terror being a new entrant to the list has characterized regional security complex imbibing global security complex concerns. Af-Pak zone is the linkage between regional and global security architecture, so far as the Global War Against Terrorism (GWAT) remains a valid agenda among community of States. This also brings in the role of special partnerships, such as, the strategic partnerships between India-US, India-Afghanistan and Afghanistan-US. Pakistan too has mechanisms of understanding with the US and Afghanistan, but there are multiplicity of channels and parallel communication with the Army and the Civilian Government in Pakistan. The multiplicity of institutions in Pakistan renders a difficult situation to deal with the terrorism.

Reconciliation and Regional Stability

Pakistani Senator Farhatullah Babar in April 2014 harangued for end to the duplicity in the foreign policy of Pakistan. He read out article 40 of the Constitution of Pakistan in the National Assembly and called for reining in of the Army and ISI, who have acted in contravention to the spirit of the Constitution.10 The mutual suspicion is rife among the security establishment of both countries. The killing of Ustad Rabbani in September 2011 was clear hiatus in any trustful relationship when Afghan President Karzai clearly pointed finger across border.11 Afghan reconciliation process has been one of the most intriguing feature of bilateral relations. The role of Pashtun groups and their complaints against the purported dominance of Tajik-led coalition in power sharing has been contested and well capitalised by Taliban to highlight the alienation. The second aspect is the agenda of Islamization of Afghanistan that Taliban seeks something which is fundamentally rejected by majority of Afghans.12 The February 2015 meeting between President Ghani and Prime Minister Sharif looked for the ways to start a tangible dialogue between Afghan delegations and the Taliban leaders.13 The initiative remains in line with last year’s overture by Taliban to rengage itself with Afghan government. Taliban leader Agha Jan Mutasim, a close aide of Mullah Omar in February 2014 announced the re-opening the Doha process that reached a deadlock in 2013 over questions of sovereign office of Taliban.14 The peace talks have had several trilateral parties of engagement. The Turkish leaders too initiated a process to bring on table Afghanistan, Pakistan and Taliban office bearers. It is interesting that Pakistan harbours most of the Taliban leadership but is reticent over the Afghan request of allowing Taliban to open office in Pakistan.15 Pakistan allowed showcasing of peace talks in November 2013 when it allowed the members of High Peace Council (HPC) to meet Mullah Baradar, who was one of the key Taliban leaders to establish contact eluding the Pakistani military establishment.16

The peace process has two more coordinates to reference to, notably, the religious parties of Pakistan, who have been pursuing their own interest in the muddled waters. The Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam-Fazl (JUI-F) Chief, Maulana Fazlur Rehman said that doubt over Pakistan’s intentions are uncalled for and gave call for religious authorities to bring peace to the region.17 The training of militants in madrasas of Khyber Pakhtunwa has been one of the feeding process to isurgency both across Af-Pak. The institutions such as Jamat ud-Dawa and Ghazi Force look for funds and young boys to be trained for militancy. The linkages of these groups with Haqqani network and Lashker I-Taiyaba creates a wider threatening scenario.18 The religious political parties so far have refrained in calling these acts as unIslamic possibly fearing their wrath. It is believed that JUI-F has influence on Hekmatyar’s Hizb I-Islami and Haqqani network.19 Their leader Maulana F Rahaman went to the extent of legitimizing the acts of terrorism in Afghanistan in the name of jihad.20 Secondly, the border clashes between Afghan security forces and Pakistan defence forces shelling villages on Afghan side have their detriments too. The cross-border movement of Pakistan Taliban after perpetrating some of the worst attacks have created severe strain on the non-charlatan approach to reconciliation. It has the component of US-led aerial strike as factor to affect the reconciliation process. The November 2011 airstrike jolted the Pakistani State and it later took the matter to the UN, over gross violation of its sovereignty.21 Such strikes have raised the barometer of distrust during Afghan-Pakistan talks. Pakistan suspects Afghanistan owing to its closeness with India and also the ability to cross-over after terror attack by Tehrik I-Taliban insurgents. The December 2014 Peshawar carnage brought chilling reality about the need to bridge the trust gap and work for sanitizing the Durand Line.22 So far, the exchange of non-State actors held in each other’s custody are released as part of calibrated strategy of mutual gain. Afghanistan in order to improve its trust with Pakistan handed over Latif Mehsud, the number two in TTP hierarchy prior to the Peshawar attack.23 Afghanistan has sought better access to Taliban captives for wider engagement under the reconciliation process. There appears reticence towards joint operations, however, the counter-terror operations have intensified by both Pakistan Army and Afghan National Army. The Mastol pass hitherto facilitating the cross-over was captured by Pak army in March 2015.24 It is believed that more such restrictions once in place shall provide a better climate for initiating the peace process.

So, far, the bilateral efforts have failed to deliver much in terms of peace and reconciliation in Afghan-Pakistan region. The Doha process was one such marked effort that brought out international effort to bring in peace in the region. The Doha Conference was successor to the 2010 January London Conference and the 2011 November Istanbul Conference. The preambulatory idea was to enable the Afghan government to engage the Taliban and seek reconciliation. The efforts were to co-opt regional partner’s for stabilization process notably Pakistan. The focus on Pakistan remained inevitable as it housed all the Taliban factions and in fact, many scholars considered it a part of the problem. Therefore, a neutral venue, such as, Doha was identified where the negotiations could be held. The idea had British and the American backing as several of the key Taliban leaders were released from Guantanomo Bay prison for talks. The five Taliban leaders were agreed upon for release by the Afghan government and the US authorities. Among them, Mullah Khairollah Khairkhwa, the interior minister during Taliban rule, Nurollah Nuri, the governor and Mullah Fazl Akhond, the chief of staff during Taliban rule were released and sent to Qatar for talks.25 The talks were a non-starter as immediately there was a protest and back out by Afghan government under the leadership of President Karzai, who categorically rejected any attempt to territorialy bifurcate the governance in Afghanistan. More so, there was total unity between the government and Abullah Abdullah led-National Coalition over any possible attempts to provide alley to Taliban who had not accepted the Afghan Constitution.

The Doha debacle brought many lessons for Afghans as the infighting was seen as a bigger threat than Taliban per se. The failure led to the spate of killings of high profile Afghan civilians and uniformed personnel viz., attack on Kabul Police in November 2014. The attacks on international presence also intensified with India facing the heat in Jalalabad and Herat. The Afghan institutions of democracy also came under attack. The most notable had been during the month of April 2014 at the time of the Presidential elections. The attack on Afghan election commission building and Serena Hotel drew worldwide attention. The Taliban too suffered one of the heaviest losses during the election year.26 The fact remained that Taliban and their Pakistani patrons were not able to secure the bargain they hoped for in the aftermath of the London Conference. Their disappointment at the hands of the Afghan government also brought for the newly gained confidence by Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police in dealing with the national security challenge. The ability to tackle insurgency with the growing success rate and also the drone warfare is showing signs of increment in counter-insurgency operations.

Pakistan has faced some of the most audacious attacks from Pakistan Taliban, such as, the 2014 September Karachi naval dockyard attack, the 2014 January Bannu attack in which more than two dozen troops were killed. These attacks reached the zenith with Peshawar attack which made Pakistan Army Chief Raheel Sharif to announce cleaning up operation against Pakistan Taliban. Pakistan also lifted death penalty in its aftermath to avenge the carnage.27 The January 2015 saw reinvigorated efforts to layout a framework for Af-Pak stabilization. Pakistan told the warring factions of ‘good’ Taliban, notably, led by Akhtar Mohammad Mansour, and commander Abdul Qayum Zakir to change gears, as it is time now to engage with the Afghan government. This has been a drastic side-step from hitherto pursued strategic asset policy. The major change is owed to growing involvement of China in the South Asian region. China has been often accused of being the reaper of benefits, instead of being the bearer of the costs, appears to set ready for much larger role in Af-Pak stabilization process. But, this surely doesn’t mean military presence; in fact, China, would wish to use economic incentive for consolidating the strategies of both the governments of Afghanistan and Pakistan. This can be an even more favourable situation if India and China also forge a win-win deal on military situation on Sino-Indian border, together with converging interest in Af-Pak region. The January 2015 media reports cited the visit of Afghan Taliban to China and possible setting of the stage for peace initiative.28 This can be seen from the context of Istanbul initiative that was hosted in 2014 by China. China also promised $2 billion dollar of assistance through 2017 to visiting President Ghani. Close on the heels of the Chinese President’s visit to Pakistan in April 2014 has seen China offering Pakistan the help to bring in the trust through its bonanza offer of economic investments. In fact, China views its investments in Afghanistan only to be further linked to its proposed $46 billion dollar investments in Pakistan. Pakistan would be a hub for China’s economic outreach in Iran and Afghanistan.29 This has its own ripple effects in the South Asian region as it destabilises the Indo-Pak trust equilibrium. Afghanistan looks for the Indian arms shipment for combating terrorism, which again spirals into destabilising Af-Pak trust equilibrium.

Conclusion

The quest for peace in Afghan-Pakistan region has often brought in the temptation of viewing the crises as zero-sum game, wherein on-off India has been factored due to periodicity and magnitude of hostility between India and Pakistan. These have excluded the various other subtler perspectives which refer to putative geo-cultural rationale for peace and stabilization of the Af-Pak region. The economic opportunity that was vied as harbinger to geopolitical motives of Pakistani establishment in tandem with the Taliban, in any case represented a natural case of South Asia and Central Asian connect. The plethora of transregional opportunity lay that could significantly raise the opportunity cost for the parties that see war economy as one of the choices. The transport network from Afghanistan exits in three directions, namely, towards, Iran, Pakistan and Central Asian States. There is need to broad-base these corridors with involvement of multiple players, who can bring in wider economic engagement. The role of India in linking with the Af-Pak trade and transit apparatus is a natural case. However, the present situation is such that India is actually working with Iran for the development of Chahbahar port that provides access to Afghanistan and Central Asia. This defies the obvious logic, but India-Pakistan conflict has its detriments to larger engagement of Afghan with South Asian region. The case with Central Asia is much better, as there is already train and road connectivity that is operating along the Amu Darya river. The Chinese oil companies have also connected the oil extraction in Sar I-pul, with refining facility in Turkmenistan. The Hairatan-Mazar I-Sharif railway connection completed in 2011 now facilitates the movement of goods to and from Central Asia to Afghanistan. The North-South Corridor is seen an opportunity for Afghanistan, to serve as transit point for Euro-Asian transport network. It is unfortunate that the economic opportunity available in South Asia has been more often used as a tool for extracting political benefits. The landlocked status of Afghanistan makes for an umbilical connection with Pakistan. The 1965 Afghan Trade and Transit Agreement (ATTA) has been the leverage tool for Pakistan, whenever it felt the need to coerce in its strategic interest within the Afghan policy framework. But, these agreements have hardly paved for increase in formal trade and much of the bulk has been traded through illegal trading points, either in Khyber or Kunar worth more than 2 billion dollars. The revised agreements signed as APTTA in 2011 aims at increasing the legal trade and discourage smuggling.30 There is a need to exit out of bilateralism in trading agreements as the political vicissitudes make them vulnerable. The recent expansion of APTTA to PATTTTA (Pakistan Afghanistan Tajikistan Trilateral Trade and Transit Agreement) that involves Tajikistan as regional partner to Af-Pak trading arrangements is a better guarantee. But, these high flyers need to be assessed in the wake of ground realities. The APTTA stock taking report has already indicated that Pakistan has failed to take advantage and similarly, Afghanistan has been languishing for want of easy access to India. The Afghan trade to the extent of 70 per cent has shifted to Bander Abbas since the signing of the trade agreement.31 The expansion of PATTTTA can be an opportunity for India and Pakistan to mitigate their mutual hostility and look for consolidating partnership that enable them to handle their respective bilateral challenges equally.32 India would be looking for extending its connectivity with Tajikistan as already CASA-1000 seems to be stuck and PATTTTA can be an opportunity to boost that project.

The President of Afghanistan is on a maiden visit to India in the month of April 2015, that looks for major steps towards expanding trade and security ties. India certainly does not pin the exclusivity of Indo-Afghan ties against the larger regional initiative that aims at stabilizing the Af-Pak region. The importance of India to contribute to the stabilisation process cannot be underestimated, as the South Asia being Indo-centric reality cannot be defaced from the larger geoeconomic array of interests. It would do no good to supplant this from any possible Chinese overtures that are only polarising set of interests rather than contributing to regional organisation of common economic and political objectives. There is a lot of goodwill that India enjoys in the hearts and minds of Afghans and it is a dividend that cannot be deterred by the hostilities between Afghanistan and Pakistan. There is enough potential for India and Pakistan to make a calibrated progress towards consolidating regional partnerships. The current visit of the Afghan President only underscores this that Afghanistan-India-Pakistan can be a foundation stone for the larger South-Central Asian inter-regional economic cooperation, that can further add up to a larger Asian economic order.

Notes

1. Ahmed, A., 2013. The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror

Became a Global War on Tribal

Islam, Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

2. Khan, A. & Wagner, C., 2013. The changing character of the Durand Line. Strategic Studies, 32(4&1), pp.19–32.

3. Omrani, B., 2009. the Durand Line: History and Problems of the

Afghan-Pakistan Border. Asian Affairs, 40(2),

pp.177–195.

4. Mahmud, T., 2010. Colonial Cartographies, Postcolonial Borders, and Enduring

Failures of International Law:

The Unending Wars Along the Afghan-Pakistan Frontier. Brooklyn Journal of

International Law, 36(1), pp.1–74.

5. Majeed, G., 2013. South Asian Security Compulsions: A Historical Analysis of

India-Pakistan Relations. Journal

of Political Studies, 20(2), pp.219–232.

6. Jalal, A., 1999. Identity crisis (in South Asia). Harvard International Review, Summer(3), pp.82–85.

7. Gady, F.-S., 2015. India and Pakistan Locked in a Nuclear Naval Arms Race.

The Diplomat. Available at:

http://thediplomat.com/2015/03/india-and-pakistan-locked-in-a-nuclear-naval-arms-race/

[Accessed April 18,

2015].

8. KHAN, M.-U.-H., 2014. Pak-China’s Game Changer Relationships. Defence Journal, 18(4), pp.15–19.

9. Rasanayagam, A., 2003. Afghanistan: A Modern History, London: IB Tauris. p.32.

10.

Haider, M., 2014. “Pakistan must break alleged links with Afghan insurgents.”

Dawn.com. Available at:

http://www.dawn.com/news/1100749/pakistan-must-break-alleged-links-with-afghan-insurgents

[Accessed

April 21, 2015].

11.

Hussain, T. and N.H., 2011. High-profile assassination: Turban bomber kills

Afghanistan’s top peacemaker. The

Express Tribune. Available at: http://tribune.com.pk/story/256483/afghan-peace-council-head-burhanuddin-

rabbani-killed-in-kabul-bombing/ [Accessed April 21, 2015].

12. Kane, S., 2015.

SR356-Talking-with-the-Taliban-Should-the-Afghan-Constitution-Be-a-Point-of-Negotiation,

United States Institute of Peace, Washington DC. Available at: http://www.usip.org/

[Accessed April 21, 2015].

13. BBCMonitoring.com, “Ghani, Sharif exchange views on dialogue with Afghan

Taleban,” Dawn.com, 15-Feb-

2015.

14. BBCMonitoring.com, “Peace overtures indicate Afghan Taleban’s change of

heart,” The Express Tribune, 17-

Feb-2014.

15. BBCMonitoring.com, “Islamabad, Kabul agree to explore options over Taleban

political office,” The Express

Tribune, 02-Dec-2013.

16. BBCMonitoring.com, “Afghan peace delegation meets released Taleban leader in

Pakistan,” The Express

Tribune, 22-Nov-2013.

17.

BBCMonitoring.com, “Islamist leader says Karzai sought Pakistan’s help in

promoting reconciliation,” APP,

Islamabad, 19-Oct-2013.

18. BBCMonitoring.com, “Pakistan ministry says Haqqani network, charity group

not banned,” The Nation, 21-Jan-

2015.

19. BBCMonitoring.com, “Afghan paper urges peace council to speed up efforts,” Chergah, Kabul, 18-Feb-2013.

20. BBCMonitoring.com, “Report condemns Pakistani cleric’s remarks on fighting

in Afghanistan,” Afghanistan

Television, Kandahar, 17-Nov-2014.

21. BBCMonitoring.com, “Pakistan protests against NATO attack at UN meet,” APP, Islamabad, 20-Dec-2011.

22.

BBCMonitoring.com, “Sources say Taleban commander mastermind Pakistan school

attack from Afghanistan,”

Dawn.com, 17-Dec-2014.

23.

BBCMonitoring.com, “Afghanistan hands over key Taleban commander, others to

Pakistan,” Dawn.com, 07-

Dec-2014.

24.

BBCMonitoring.com, “Pakistan army regains control of pass used by militants to

escape to Afghanistan,” The

News, 24-Mar-2015.

25.

BBCMonitoring.com, “Afghan government agrees to transfer of Guantanamo Taleban

to Qatar,” Tolotv.com,

08-Feb-2012.

26.

J. Partlow, “Violence data show spike during Afghan presidential election - The

Washington Post,” 14-Apr-

2014.

27. M. Chastain, “Pakistani Army Kills 77 Taliban Members After Peshawar

Massacre - Breitbart,” Breibart.com,

20-Dec-2014.

28. S. Tiezzi, “China Hosted Afghan Taliban for Talks: Report,” The Diplomat, 07-Jan-2015.

29. S. Haider, “In step with Ghani’s Afghanistan,” The Hindu, 24-Apr-2015.

30. Cochran, V.C., 2013. A Crossroad to Economic Triumph or Terrorism: The

Afghanistan-Pakistan Transit Trade

Agreement. Global Security Studies, 4(1), pp.1–15.

31.

BBCMonitoring.com, “Pakistan-Afghan transit trade pact fails to boost bilateral

trade,” The Express Tribune,

14-Oct-2014.

32.

BBCMonitoring.com, “Scene-setter: High expectations from Afghan president’s

India visit,” BBC Monitoring

Research, 25-Apr-2015.

______________

*Dr. Ambrish Dhaka is

an Associate Professor, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru

University, New Delhi-110067; E-mail: ambijat@gmail.com; Phone: (+91)

9968234110.